Donald Ellis Recognized as a Pre-Eminent Dealer

A brief profile in Native Peoples Magazine describes Donald Ellis as one of ‘the leading figures’ in the trade of historical Native American art

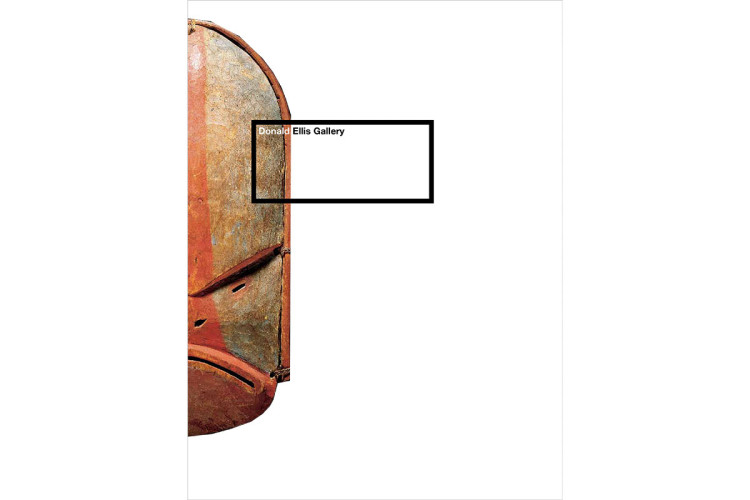

19th century

wood, paint, vegetal fibre

height: 17"

Inventory # CE3248

Sold

acquired by the Diker Collection, now at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

Donald Ellis Gallery, Dundas, ON

Private collection, Toronto, ON

Donald Ellis Gallery, New York, NY

The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection, New York, NY

“Artworks made by Canada’s First Nation and Inuit Peoples,” Canada House, London, U.K.; May 13–August 28, 1998

“Indigenous Beauty: Masterworks of American Indian Art from the Charles and Valerie Diker Collection,” Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, WA; February 12–May 17, 2015

“Indigenous Beauty: Masterworks of American Indian Art from the Charles and Valerie Diker Collection,” Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, TX; July 5–September 13, 2015

Donald Ellis Gallery catalogue, 2005, cover and pg. 11

Indigenous Beauty: Masterworks of American Indian Art from the Diker Collection, David Penney et al., New York, NY, Skira Rizzoli, 2015; pg. 73, pl. 35

Corey, Peter L. (ed.) Faces Voices and Dreams: A Celebration of the Centennial of the Sheldon Jackson Museum. Sitka: Alaska Department of Education, 1987, pl. 6

Krech, Shepard III. A Victorian Earl in the Arctic: The Travels and Collections of the Fifth Earl of Lonsdale, 1888-89. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1989, pls. 173 & 174

Very little has been recorded or collected from the Chugach peoples of south central Alaska, who lived in the area of Prince William Sound, near the mouth of the Copper River. Early contact with Russian fur traders appears to have reduced the population of already small Chugach communities, and few outsiders seem to have ventured into their territories. This contrasts with other Alaskan groups such as the Tlingit of the southeastern panhandle, or the Yup'ik and Inupiaq peoples of western Alaska, from whom a significant amount of material culture and written documentation has been gathered over the last two centuries.

Among the handful of carved masks that are known to have originated in the Prince William Sound area, this extraordinary example is perhaps the finest extant. The carving of the face, though appearing simple, is extremely engaging and visually powerful. A rich world of expression is developed with only the most elemental relief carving at the brow line, nose and mouth. The graphic quality to the cut lines of the face reveals something far deeper than the sculpture itself, and the minimal painted forms serve to develop that richness even further. The subtle use of paint includes a swath of red tapering from the upper lip to the peak of the tall forehead, and what is now but a thin transparent veil of blue pigment on the eye sockets and cheeks. The elegantly elongated form of the head appears to be related to mask forms of the neighbouring Aleut and Kodiak Island cultures.

The wooden rod encompassing the face is attached with twisted fiber via small holes cut in the edge of the mask. This bentwood surround may relate to similar wooden hoops in Yup'ik masks, a culture far to the west. Among the Yup’ik, the concept of a ‘ringed center’ was a metaphor for certain shamanistic powers, including the ability to move between the world of the living and that of the spirit. In this outstanding mask, the bentwood attachment acts visually as a passage through which the shaman would travel on his journey across the boundaries between worlds.

A brief profile in Native Peoples Magazine describes Donald Ellis as one of ‘the leading figures’ in the trade of historical Native American art

Out of print