2001

$30.00 USD

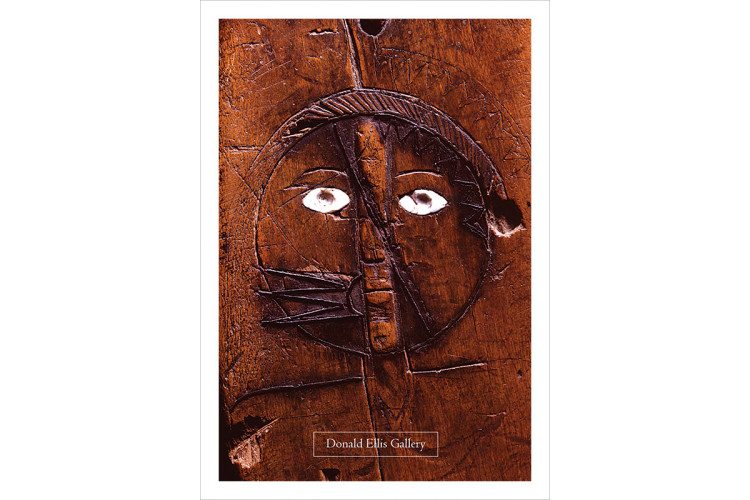

ca. 1620-1680

hardwood, brass and shell inlay

height: 24"

Inventory # CW2049

Sold

acquired by the Thaw Collection, Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, NY

Reportedly collected by Lt. John King (b 1657.), Northampton, Mass., in the late 17th century

by descent to Experience King, daughter of John King

by descent to Dr. Timothy Dwight, President of Yale University (1758-1817), grandson of Experience King

by descent to Esther Johnson Diefendorf, Summit, NJ

Formerly on long-term loan to the Museum of The American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York, NY, 1963-1996

Donald Ellis Gallery catalogue, 2001, cover and pgs. 14-15

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, England, Cat. Nos. B. no. 133-5, B. no. 134 and B. no. 135 - See: MacGregor, Arthur. Tradescant's Rarities, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1983, pg, 111, Fig. 2, for three clubs collected in in the mid 17th century by the notable traveller and naturalist John Tradescant (1608-1662)

Fruitlands Museum, Harvard, No. FM-I-OI - See: Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 15, Sturtevant Ed., Washington, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990, pg. 171, for an example displaying wampum shell inlay, and said to have belonged to King Philip

Denver Art Museum, no. Qlro-9 - See: Ibib, pg. 433, for and example featuring a similar animal carving at the haft end of the club, reportedly collected on a battlefield in 1755

Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, No. 19/4922 - See: American Indian Tomahawks, Peterson, Here Foundation, 1971, fig. 2

Very few objects remain from the Native American inhabitants of 17th century New England. Over 150 years before the expedition of Lewis and Clark (1803-1806), New England was already an established British colony. As a result, the traditional life of the indigenous population of the Northeast was undergoing profound change.

This extraordinary war club has several features that clearly place its date of manufacture to this early period. The use of brass inlay derived from broken trade kettles to decorate clubs, pipes and occasionally bowls, was a technique used in the Eastern Woodlands circa 1630 - 1660. Sheet brass obtained in trade, later replaced kettle brass. The existence of shell inlaid eyes in the human face (likely a representation of the owner), and the presence of wampum shell inlay on the concave trailing edge of the club, parallel several other clubs with 17th century collection histories (see: MacGregor, 1983 and 1987).

Remarkably, this object has remained in one family for over 300 years. According to family history, the club was collected by Lt. John King of Northampton, Massachusetts. King was 18 in 1675 when the King Philip's war began. We know that King, along with approximately 150 volunteers under Captain William Turner, assembled at Hatfield, Mass. on May 18, 1675, to recapture prisoners held on the banks of the Connecticut River west of Deerfield. It is quite possible that King collected the club during this encounter, as war clubs were often defiantly left on battlefields after successful raids. We do know that the club subsequently entered the possession of descendants of John King's daughter, Experience. Experience King's grandson, Dr. Timothy Dwight (1758-1817), president of Yale University, wrote in the early 19th century in Travels in New England & New York: "Another of their principal weapons was the well-known Tomahawk, or war-club. I had one of these in my possession many years; in shape, not unlike a Turkish sabre, but much shorter, and more clumsy. On it were formed several figures of men, by putting thin strips of copper, set edge-wise in the wood. Some of them were standing; some were prostrate; and a few had lost their heads. The last two were supposed to denote the number of enemies, whom the owner of the Tomahawk professed himself to have killed" (see: Dwight, 1821)

Rich in iconography, mysterious in its beauty, this war club is possibly the most important surviving example of Eastern Woodlands sculpture.

$30.00 USD