Donald Ellis Secures Dundas Collection at Auction

The Maine Antiques Digest reports that Donald Ellis was able to secure the majority of the Dundas collection of Northwest Coast First Nations art at auction

ca. 1840-1860

wood, paint, fibre

height: 12"

Inventory # N2978-14

Sold

acquired by the Scottish Reverend Robert J. Dundas from Anglican lay minister William Duncan in 1863 at the village of Metlakatla, British Columbia

by descent in the family

Simon Carey, London, England

Sotheby’s New York, Oct 5, 2006, lot 38

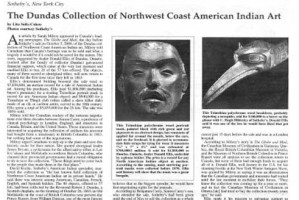

The present Naxnox mask was acquired by the Scottish Reverend Robert J. Dundas from the English lay missionary William Duncan on a trip to Canada in 1863. In 1862, Duncan had established a model Church of England mission at Old Metlakatla, an abandoned settlement near Prince Rupert, B.C. Dundas acquired almost 80 objects from Duncan, including crest helmets, rattles and antler clubs which remained in the Dundas family for several generations.

Mechanical masks with articulated eyes and mouths were common in the ceremonial known as Naxnox, which can be translated as "power beyond the human" or "spirit power", each indicating unseen forces that originate on the "dark side". Such spiritual forces are opposed to the socializing strength and sense of order established in the ancient histories of high-caste lineages, and the ritualists and chiefs that are the personification of that order. The more chaotic and powerful the negative spiritual forces are thought to be, the greater is the perception of positive spiritual strength and power in those whose ritual duties are to tame and repress the dark forces in order to strengthen the society as a whole. The performances of the Naxnox amplify the belief in those dark spirit powers, which in turn amplifies the perception of spiritual and cleansing power seen in those who manage and perform the rituals.

The overall black color and stark form and decoration on this mask is typical of the Naxnox tradition, as are the articulated eyes and beak. The opening and closing of the eyes would not only give the mask life, but would also communicate the recurring presence of negative spirit forces. The use of lines of dashing on the black painted areas is a common technique among artists in this region and generational timeframe, and is seen in many other examples of works in this collection. The series of unpainted triangular forms, also known as trigons, which create lobes of black around the brow area, are drawn from the essential elements of the ancient design tradition.

Pulleys, strings, and a wooden bite plug on the inside of the mask enable wearing the mask and manipulation of its moveable parts. About half of the upper mandible has been added on to the face of the mask, no doubt re-orienting the grain of the wood from vertical to horizontal, in order to strengthen the thin tapered end of the beak. The wood grain, the long cell fibres, are oriented horizontally in the lower mandible for the same reason, to keep the thin, fragile tip from breaking off.

The Maine Antiques Digest reports that Donald Ellis was able to secure the majority of the Dundas collection of Northwest Coast First Nations art at auction